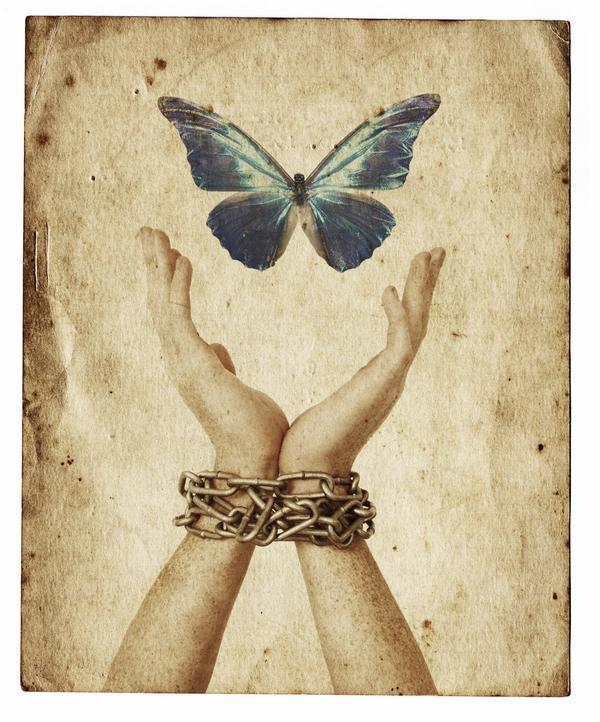

A good portion of this week's readings dealt with the idea of freedom.

What did Lenin say about freedom? What did others say to that? What is their own definition and all. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's (August 27, 1770 – November 14, 1831) core concept in life was the notion of freedom. Understanding humanity, its history, political life, and self-consciousness all revolved around this, in Hegel's work and philosophy (source). Eighteenth century philosophy of freedom dealt with the individual citizen, a strand of belief that Hegel did not subscribe to. Hegel believed that such individualistic freedom is tyrannical, and is abstract and purely formal. He said that true freedom is only possible in a political state where millions of differences in wills can be reconciled through reason.

However, as Lenin famously retorted, “Freedom yes, but for whom? To do what?” Does the ability to express one's own opinions and choices constitute freedom? One very small example can look at the scenario where parents encourage children to express their wants and listen to them (a very Western concept for me). But is that freedom? Does that child know what it entails? From here, it can be a logical deduction that freedom requires a certain degree of consciousness.

Consciousness for whom? Another example may include a group of people who are born and raised in the bourgeois class. Do they even know the plights of the proletariat? In such cases, does freedom not become a mere word to play with linguistically?

Finally, freedom that truly does not bring peace to a nation or group, cannot be a freedom to look for and crave. Freedom to not know, and fall into the hands of the cunning capitalistic and hegemonic propaganda cannot be freedom. Inability to question the status quo because of any fear of consequences cannot be freedom, even though the setting is in a free world.

So what is freedom? Do we actually have a choice?

What did Lenin say about freedom? What did others say to that? What is their own definition and all. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's (August 27, 1770 – November 14, 1831) core concept in life was the notion of freedom. Understanding humanity, its history, political life, and self-consciousness all revolved around this, in Hegel's work and philosophy (source). Eighteenth century philosophy of freedom dealt with the individual citizen, a strand of belief that Hegel did not subscribe to. Hegel believed that such individualistic freedom is tyrannical, and is abstract and purely formal. He said that true freedom is only possible in a political state where millions of differences in wills can be reconciled through reason.

However, as Lenin famously retorted, “Freedom yes, but for whom? To do what?” Does the ability to express one's own opinions and choices constitute freedom? One very small example can look at the scenario where parents encourage children to express their wants and listen to them (a very Western concept for me). But is that freedom? Does that child know what it entails? From here, it can be a logical deduction that freedom requires a certain degree of consciousness.

Consciousness for whom? Another example may include a group of people who are born and raised in the bourgeois class. Do they even know the plights of the proletariat? In such cases, does freedom not become a mere word to play with linguistically?

Finally, freedom that truly does not bring peace to a nation or group, cannot be a freedom to look for and crave. Freedom to not know, and fall into the hands of the cunning capitalistic and hegemonic propaganda cannot be freedom. Inability to question the status quo because of any fear of consequences cannot be freedom, even though the setting is in a free world.

So what is freedom? Do we actually have a choice?

Comments